The Critical Ocean Minerals Research Centre (COMRC) recently published a report titled "A Deadly Moratorium", which argues that the proposed moratorium on seabed mining come at the cost of human lives and vast environmental destruction. We've reviewed and summarised this report below:

Introduction

"A Deadly Moratorium" is fundamentally a call to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), along with other Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), large corporations and governments, to withdraw their support for a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

The report argues that this moratorium is forcing the world to double down on some of the worst practises for extracting critical minerals. In particular it argues that demand for these minerals is causing significant damage to some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet; is causing death, disease and displacement to vulnerable indigenous peoples; and is increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

This report seeks a broader dialogue around how the world meets demand for critical minerals, and particularly how we approach deep-sea mining of polymetallic nodules as a potential source of these critical minerals. We'll discuss this more below:

Democratic Republic of Congo, May 2009. (Tom Stoddart/Getty Images)

Democratic Republic of Congo, May 2009. (Tom Stoddart/Getty Images)

Impact of Terrestrial Mining

One of the key points raised within this report is that current terrestrial mining for critical minerals has a huge impact on some of the most sensitive, biodiverse, and fragile ecosystems on our planet.

Items of concern that are raised include:

- Terrestrial mining has a large direct impact - around 15,000 miners die each year

- However, indirect impacts of terrestrial mining are far more widespread

- Terrestrial mines generate large quantities of toxic solid waste

- An estimated 23 million people live on floodplains contaminated by mining

- Many critical minerals are mined in areas with high biodiversity, including rainforests

Terrestrial mining of critical minerals increasingly occurs in equatorial countries, often in areas with rainforests and indigenous peoples, and it has huge and terrible impacts on these peoples and ecosystems.

Furthermore, the impacts of terrestrial mining are not broadly understood by the general public, particularly more developed nations like the US or those in Europe. Mining standards and practises vary by country, and public discourse does not take into account these impacts as they are often not seen or understood.

Open pit mine in Mindanao, Philippines with clearly visible tailings. (iStock/Mary Grace Varela)

Open pit mine in Mindanao, Philippines with clearly visible tailings. (iStock/Mary Grace Varela)

People from the Mura tribe are pictured in a deforested area in unmarked Indigenous lands inside the Amazon rainforest near Humaita, Brazil.

People from the Mura tribe are pictured in a deforested area in unmarked Indigenous lands inside the Amazon rainforest near Humaita, Brazil.

A terrestrial nickel mine in Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 09, 2021. (iStock/Adhitya Nur)

A terrestrial nickel mine in Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 09, 2021. (iStock/Adhitya Nur)

Comparison with Deep-Sea Mining

The report acknowledges that it is prudent to approach deep-sea mining with caution as there is no precedent for commercial-scale extraction from the deep abyssal plains. The technology and processes are new, which means that are various uncertainties and precautionary measures must be taken.

However, the main point that the report makes is that these uncertainties cannot be viewed in isolation, and that they must be weighed against the known, widespread and harmful impacts of terrestrial mining.

Furthermore, the report points to over 50 years' worth of research and work that has been done on the impacts of collecting polymetallic nodules.

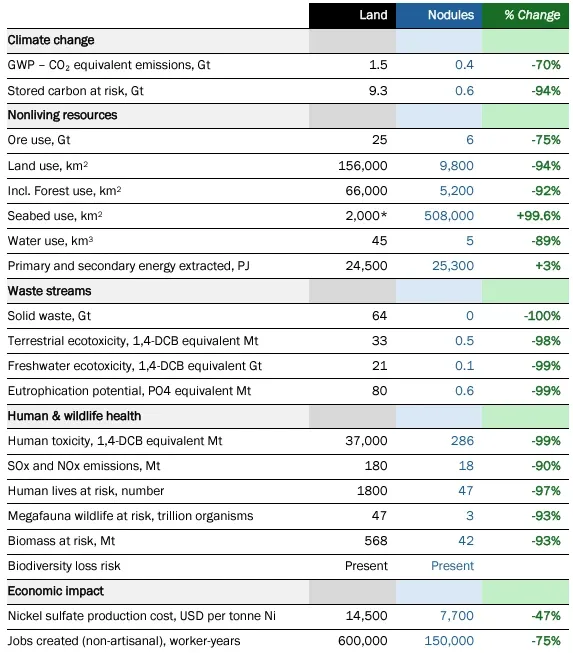

Comparison of deep-sea mining to terrestrial mining. (Paulikas, 2020)

Comparison of deep-sea mining to terrestrial mining. (Paulikas, 2020)

Issues with the "Precautionary Approach"

Opponents of deep-sea mining often cite a need for precaution, stating that there is a lack of understanding of the impacts of these activities. However, the precautionary approach calls for the evaluation of both the costs and benefits of an action - both of action and lack of action - in both the short and long term.

"Deadly Moratorium" argues that NGOs and groups calling for a deep-sea mining moratorium are effectively only looking at the potential cost of action. They don't look at the impact of inaction - that is, continued and growing terrestrial mining activity in areas of high biodiversity, fragile ecosystems and indigenous peoples.

Summary

Deep-sea mining of polymetallic nodules is potentially a huge source of critical minerals that are needed for the green energy transition. These resources are abundant, accessible and can be produced with relatively little impact.

Given rapidly growing demand for critical minerals worldwide, along with the significant impact of terrestrial mining on fragile peoples and ecosystems, the report concludes that continuing calls for a moratorium on deep-sea mining are both deeply harmful, and fundamentally at odds with the principle of a Precautionary Approach, as is often cited.