Introduction

As companies approach the exploitation phase of Deep Sea Mining, one critical factor is the transportation of mineral ores from the mine site location to onshore refineries.

Whilst this may appear to be a relatively simple step, involving conventional bulk ore carriers and standard procedures, the nuances and practical limits of operating in the deep ocean mean that this step becomes increasingly complex and challenging. This article will explore the STARS concept, the likely regulatory requirements, and the complexities of this new vessel type.

Unfortunately, many stakeholders have overlooked the importance of this link in the production process, and challenges around shipyard availability and lead times mean that the timing of delivery of STARS vessels is critical to the success of projects.

STARS Concept

Most proposals for deep sea mining involve using a large Production Support Vessel (PSV) to operate the mining equipment (including Harvester, RALS, surface separators etc) that stays on the mine site location. This necessitates a shuttle type of transporter to transfer harvested nodules to the designated offloading site. These operations would be superficially analogous the use of shuttle (oil) tankers offloading FPSOs in the oil and gas industry.

Whilst it might seem feasible to simply modify a standard bulk carrier for this purpose, this type of shuttle transporter requires significant thought on the part of designers and operators around efficiency and regulatory compliance. These additional requirements mean that the industry regards them as a distinctly different type of vessel, and they have acquired the acronym STARS (Shuttle Transport And Resupply Ship)

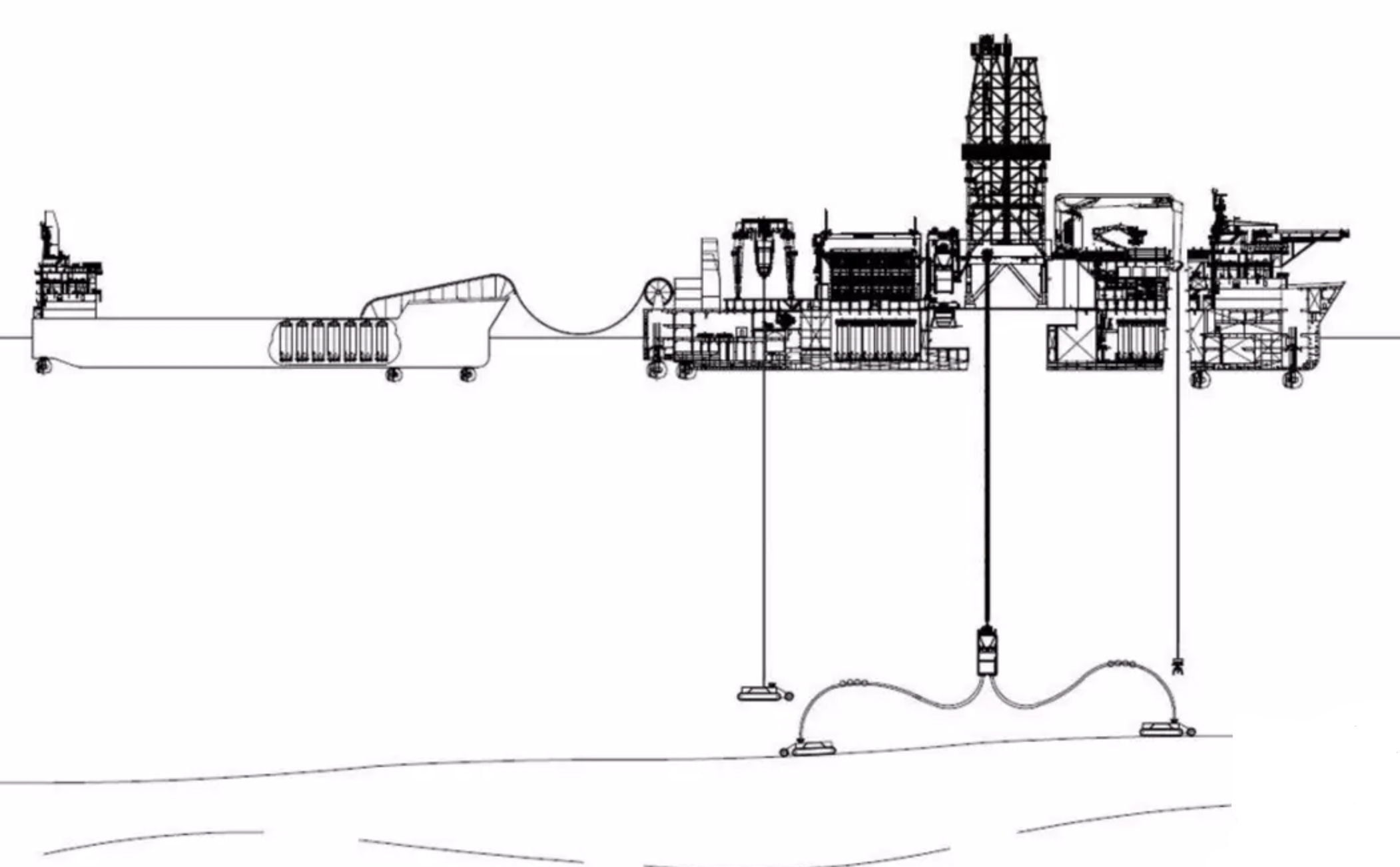

Schematic by NOV (Guido Van Den Bos) of a Production Support Vessel with RALS and Harvesters deployed, offloading to a STARS via tandem (line-astern) offloading.

Schematic by NOV (Guido Van Den Bos) of a Production Support Vessel with RALS and Harvesters deployed, offloading to a STARS via tandem (line-astern) offloading.

STARS Considerations

In general, a STARS vessel will likely be expected to fulfill 4 key tasks:

- Transfer of nodules from the PSV

- Transport of those nodules to the processing facility

- Transport of equipment, fuel and provisions to the PSV

- Transfer of personnel to and from the PSV per crew rotas

Of these 4 tasks, the receipt of nodules, transport of fuel, and the transfer of personnel raise several challenges, particularly around Standards and Regulations. These impact the ability to insure the vessels and operations, and consequently impact financing of the project or company.

The nuances and complexities of these tasks are outlined below:

Ship-to-Ship Transfers

There are several options for transferring nodules from the hold of the PSV to the STARS, including wet or dry transfer, via hose or conveyor, and with the vessels alongside or astern of each other. Each of these options has a several advantages and disadvantages, discussed below:

Tandem (Line Astern) Offloading

STARS maneuvers to hold position astern of the PSV, and nodule transfer is made from the stern of the PSV to the bow of the STARS

Example from oil & gas of an FPSO offloading

Example from oil & gas of an FPSO offloading

Pros:

- Weather window is greater, increasing operational uptime

- May not require vessels with Dynamic Positioning (DP)

Cons:

- STARS must constantly maneuver to hold position if the PSV is actively mining, as the PSV must follow a pre-determined mining pattern and cannot “weather-vane”

- Likely necessitates the use of slurry transfer via hose, with significant issues (see below)

- STARS must still come alongside for refueling and replenishment

Side-by-Side (Alongside) Offloading

STARS maneuvers alongside the PSV, lines go across, STARS is secured alongside the PSV on Yokohama type fenders. Nodule transfer is made from the side of one vessel to the other

Example of alongside transfer at sea

Example of alongside transfer at sea

Pros:

- Allows for simultaneous cargo loading, replenishment, refueling and crew-change

- Greater range of nodule transfer options, including dry / conveyor

- PSV may continue mining while offloading

Cons:

- Greater risk of collision than tandem offloading method

- Weather window may limit side-by-side mooring

- More training and effort required from crews

- May interfere with Harvester Launch and Recovery Systems (LARS) or ROV umbilicals

In each case, the ship-to-ship transfer of dry goods requires coordinated maneuvering of an approximately 100,000t PSV (typically following a pre-determined track at a speed of around 0.5knots ground speed) with a 25,000-100,000t bulk ore carrier. This is relatively unprecedented in maritime operations.

Furthermore, whilst OCIMF / SIGTTO has published the “Ship to Ship transfer Guide for Petroleum, Chemicals and Liquefied Gases” (to advise Masters, Mariners and others in ship-to-ship transfer), as of now, no organization has guidance for dry cargo transfer at sea. It is hoped that the new International Subsea Minerals Academy (ISMA) based at the Texas Laboratory for Ocean Engineering might take on developing this new and needed standard.

Nodule Transfer Methods

Further to these maneuvering requirements, 2 broad categories of nodule transfer have been proposed, each of which brings challenges and limitations:

Wet Transfer

Nodule slurry is pumped via hose from the PSV to the STARS

Example of hose offloading from an FPSO

Example of hose offloading from an FPSO

Pros:

- Hose has longer length and greater flexibility

- Can be used with either Tandem or Side-by-Side offloading

Cons:

- Requires dewatering equipment to be installed on the STARS

- Water must then be returned to the PSV for reinjection at depth, requiring significant extra equipment, handling, and connections between the 2 vessels

Dry Transfer

Nodules are transferred via cargo conveyor

Example of conveyor offloading for iron ore

Example of conveyor offloading for iron ore

Pros:

- Simpler, as dewatering occurs on the PSV and extra handling equipment is not required on the STARS

Cons:

- Transfer distances are shorter and equipment is less tolerant to errors

- More appropriate for use in Side-by-Side offloading

- Weight and costs increase significantly as offset distances increase

Although these options both present several challenges and issues, the wet transfer method is generally seen as unacceptable and Operators are aligning on using dry transfer. Significant volumes of water are lifted to surface with nodules from the seabed. This water is very different in temperature and chemical composition to water at the surface, and environmental studies indicate that it should not be discharged at surface. Consequently the separated water is returned to depth via return line on the PSV.

Transport of Equipment, Fuel, Provisions and Personnel

Polymetallic Nodule are mostly found on the vast, deep abyssal plains of the global ocean. In most instances, nodule fields are located at great distances from land; ranging from around 100-150nm from land in the Penrhyn Basin of the Cook Islands EEZ, to thousands of miles from land in some parts of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Northern Pacific. Consequently, transport distances, times and practicalities are of major consideration.

If a deep sea mining mine site is within practical helicopter flight or sailing distance, then equipment, provisions and crew transfers may be best accomplished from the shore base by conventional helicopter and/or platform supply vessel transfers.

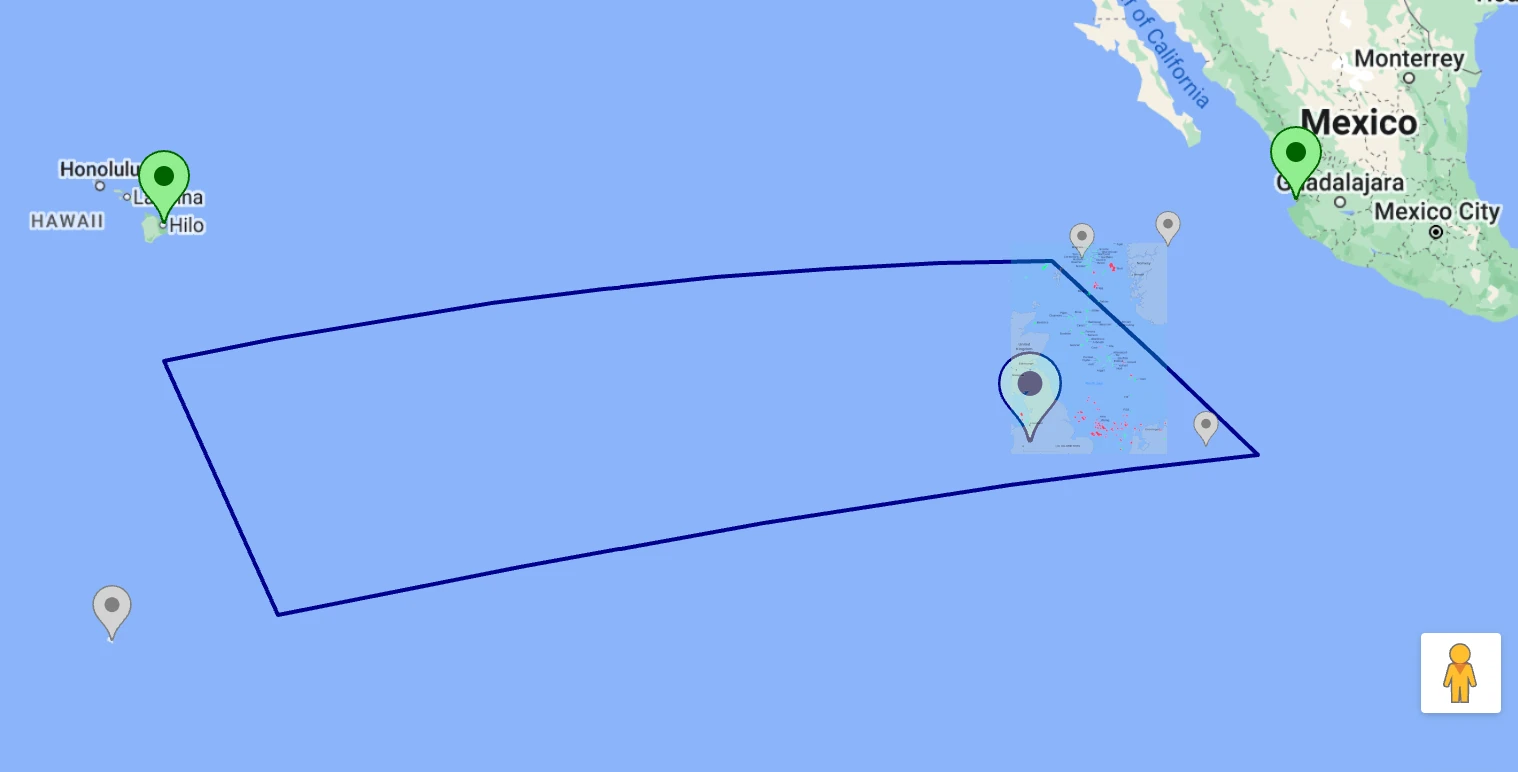

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is vastly more remote than most areas of current offshore operations. Here, a map of the North Sea is superimposed upon a map of the CCZ.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is vastly more remote than most areas of current offshore operations. Here, a map of the North Sea is superimposed upon a map of the CCZ.

However, many of the International Areas are impractical for a platform supply vessel and impossible to helicopters to reach. Therefore the most economical way to resupply the PSV would be to adapt the STARS as a cargo transport vessel to also accomplish these auxiliary missions.

The STARS role would thus expand to include:

- Transport of solid cargo, provisions and equipment

- Transport and transfer of fuel

- Transport and accommodation of personnel (likely between 10 and 30 per transfer, depending upon rotas, crew requirements and frequency of resupply)

These additional requirements in turn add further complexities and challenges, such as the need to use a “Billy Pugh” or other personnel transfer methods, along with regulatory requirements for increased stability and survivability for fuel-carrying vessels, and safety and accommodation requirements for personnel. These are outlined below:

Regulatory Issues Around Industrial Personnel

In November of 2022 the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC 106) adopted a new mandatory safety code for ships carrying “industrial personnel”.

The new Chapter XV of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and the associated new International Code of Safety for Ships Carrying Industrial Personnel (IP Code) aim to provide minimum safety standards for ships carrying industrial personnel (as well as for the personnel themselves) and address specific risks of maritime operations within the offshore and energy sectors, such as personnel transfer operations.

The amendments and code are expected to enter into force on July 1st 2024, and will require ships of > 500 gross tonnage to have an Industrial Personnel Safety Certificate (IP Certificate) if they carry more than 12 Industrial Personnel. These criteria will likely be exceeded by a STARS vessel, and the requirements will likely not be met by existing bulk ore carriers.

Regulatory Issues Around Refueling

If STARS vessels are to be used to refuel the PSV, then certain aspects of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) will also apply to STARS.

These requirements include specifics around cargo oil tank construction, subdivision, piping and oil/water separation arrangements.

Conventional bulk ore carriers would not meet these requirements as they do not refuel other vessels. Furthermore their design optimizes for bulk carriage, rather than the sub-division and flooding protection that MARPOL typically requires. Consequently significant retrofitting would be required of conventional bulk carriers.

Options - New Construction or Major Refit

As with any other engineering design calculation, cost and scheduling constraints will be major considerations. On the cost side, an existing handy or handymax bulk carrier can be readily purchased on the second hand market. However, extensive hull and machinery modifications would be required in order to meet the minimum requirements of Dynamic Positioning , IP code and Marpol tanker.

Conclusion

Shipment of bulk polymetallic nodules from a deep sea mining mine site appears at first glance to be a relatively simple issue, requiring the use of standard bulk ore carriers with minor modifications. However, the combination of remote mine-sites, long distances and complex supply-chains means that the STARS vessels are expected to do far more work than a typical bulk ore carrier.

Operating complexities, including combinations of pre-determined sub-optimal courses, large unhandy vessels, and tight offloading criteria, mean that the process of offloading bulk nodules is complex. These operations likely necessitate the retrofitting of thruster pods and DP2 capabilities to existing ore carriers, whilst the operations themselves are unprecedented and currently lack regulations.

Further logistical optimizations, such as the use of the STARS to transport food, fuel, equipment, and personnel, further complicate the operations. These trigger provisions in SOLAS and MARPOL which require significant design modifications for regulatory adherence.

The result is that retrofitting existing bulk ore carriers into STARS is likely to be prohibitively complex and expensive, and it seems likely that a new purpose built type of vessel will be needed to meet these needs. However, design and construction lead times (particularly availability of shipyard space) mean that these vessels are increasingly becoming the limiting factor for successful deep sea mining operations.

As with the PSV, the American Bureau of Shipping has done a great deal of groundwork on the regulatory compliance aspect of the STARS vessels. The publishing of the “Requirements for Subsea Mining” was the first and until now, the only Classification Society Rules for this industry. It is expected that in the future a new vessel designation such Supply Transport and Resupply Vessel will be accepted by Flag States and by the DSM regulatory bodies (ISA, Cook Is SBMA etal.) much as Subsea Mining Vessel was accepted for the Alllseas Hidden Gem.

In order to be successful, DSM stakeholders need to carefully consider this “missing link” in their supply chain.